Although the area around Armitage Avenue and Halsted Street in western Lincoln Park was subdivided in the 1850s when it was annexed by the city of Chicago it remained somewhat rural until after the Great Fire of 1871. The fire had missed this area by a few blocks and many residents who lived further east decided to rebuild in the untouched western portion. The rebuilding after the fire was the first of three development waves that would change this parcel of farms and nurseries into a vibrant German neighborhood and commercial district, then a run-down patch of derelict stores and homes and finally into one of the most wealthy communities in Chicago.

Armitage Avenue (known as Center Street until the early 1900s) and Halsted Street are arterial roads and hence carry heavier traffic and are lined with many commercial establishments. In 2002 the city of Chicago named 7 blocks of W. Armitage and 3 blocks of N. Halsted Street as a formal Historic District. Among other reasons the city’s Commission on Landmarks cited the “ solid and exceptional core of Victorian-era buildings, replete with pressed-metal cornices, bay windows and turrets, terra-cotta ornament, and brick and stone patterning that give an onlooker an excellent feel for the intimate scale, visual eclecticism, and beauty of the commercial architecture that once graced Chicago’s oldest neighborhoods.”

View of Armitage Avenue rooftops looking east from Bissell Street.

The next two waves of development, in the 1880s and then again a decade later, were transportation-related. In the 1880s cable cars then electrified street cars began to operate on Armitage, Halsted or nearby streets creating a commuter environment to downtown jobs. This spurred the development of commercial establishments along the arterial streets. Then on January 8, 1894 Chicago granted a franchise to the Northwestern Elevated Railroad Company to build a rail line from downtown to Wilson Avenue that would include a station stop at Armitage/Center near Sheffield Avenue.

Armitage ‘L’ Station, opened June 9, 1900. Designed by William Gibb.

The ‘L’ station was refurbished in 2007 - 2008 as part of the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project. To expand the station platform the city purchased the building across the street from the ‘L’ station at 939 W. Armitage. The construction team sliced off the western portion of the structure, but preserved the eastern section due to the building’s contributing status to the historic district .

939 W. Armitage Avenue. William Schaefer, developer (1892)

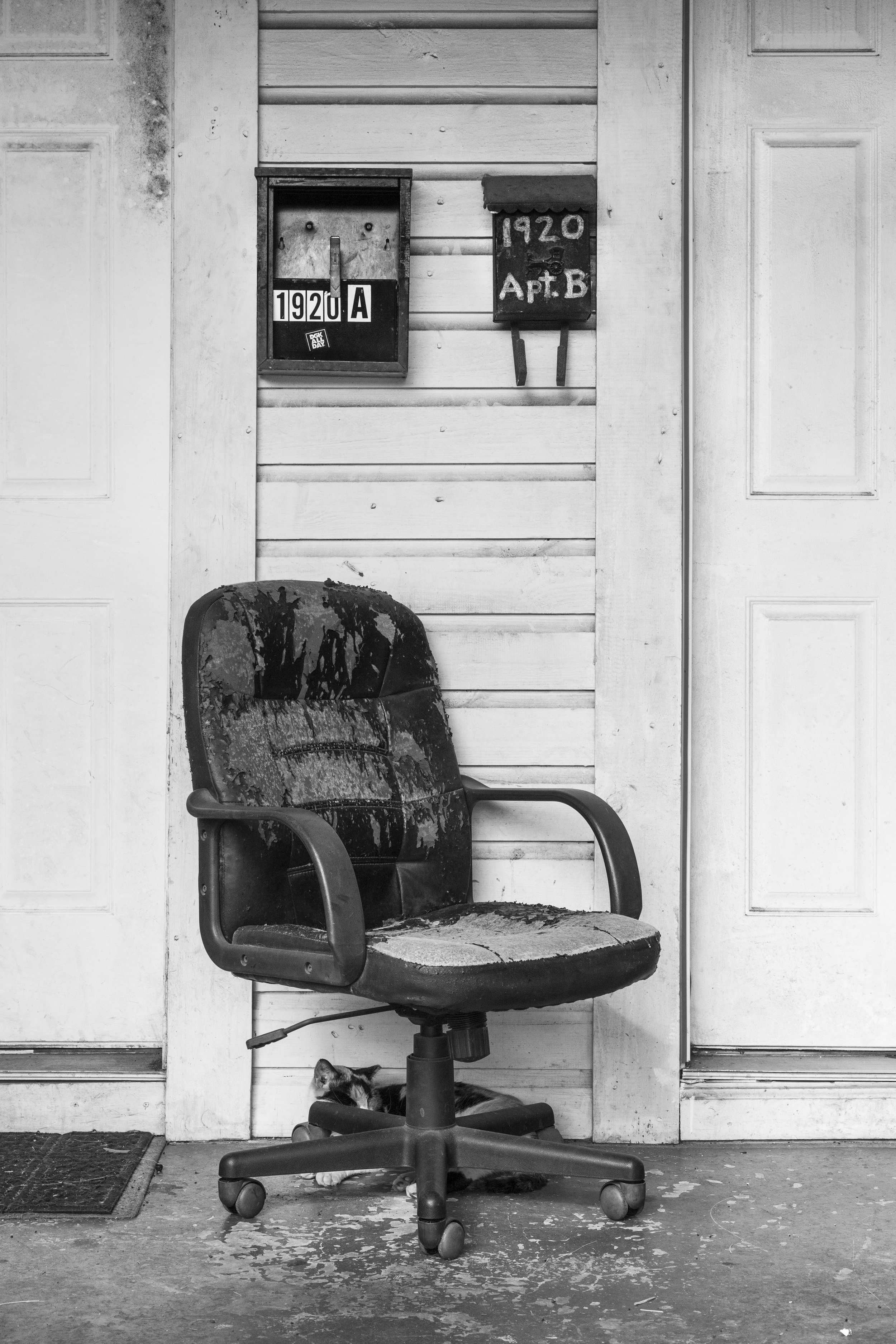

The standard design practice at this time which later became codified in the area’s zoning ordinances called for retail establishments on the first floor with apartments on the floors above. A typical example of this can be seen below in the building at 1912 N. Halsted Street.

The district’s stretch along Halsted Street includes some notable and locally well-known buildings (see slide show below). For example,1966 N. Halsted Street, currently home to the popular Pasta Palazzo restaurant, includes some Louis-Sullivan inspired terra cotta panels on its facade. This is one of the “newer” buildings in the historic district, designed in 1924 by architect B.J. Burns.

Just up the street at the actual intersection of Halsted and Armitage sits the 2000-2002 N. Halsted Building (again, see slide show below), an imposing 4-story brick commercial and residential structure developed by Charles Nissen1884. Nissen, like several developers in the district, placed his name in perpetuity on the building’s cornice.

One of my favorite buildings is the former Chicago police station located at 2126 - 2128 N. Halsted. It is one of the oldest remaining police stations in the city, built in 1888 (the date is carved into the cornice) and it served as headquarters for the 40th Precinct. However, by the 1930s, it was sold by the city and became an American Legion hall. It’s simple Italianate design belies a recently-renovated luxury condo unit on the upper floors.

Perhaps the most-recognized building on the Halsted stretch is the 4-story brick commercial and residential building on the northwest corner with Dickens Street (formerly Garfield Avenue) best known for its tall, white corner turret. The building was designed in 1888 by architect John Schnoor for the owner Louis Berthal at a cost of $30,000. For years the building housed the much-loved French restaurant Cafe Bernard which was opened by Sue Gin in partnership with Marty Shuster and French chef Bernard LeCoq back in 1972. The cafe rejected the stuffy reputation of many French restaurants, but still played a role in the transition to the neighborhood’s current upscale status.

Several other buildings along the west side of Halsted Street contribute to the historic district with the run back down to Armitage as seen below.

The west side of the 2100 block of Halsted Street looking south towards Armitage Avenue.

While the three blocks of Halsted Street (primarily along the west side of the street) add to the district’s charm, the vibrant nature of the architecture really shows up along Armitage Avenue where contributing buildings line both sides of the street.

Armitage Avenue looking east from the ‘L’ station platform on an empty Christmas Day.

Walking west, towards the ‘L’ tracks from the intersection of Armitage and Halsted the first building most people notice is 825 W. Armitage on the southeast corner with Dayton Street. Built in 1891 by developer D. R. Rothrock the four-story mixed-use building features an elaborate corner turret and supporting column with projecting square bay windows along the Dayton Street facade.

Walking along Armitage reveals the plethora of design details that mark the historic district - the pressed-metal cornices; the jutting, elaborate bay windows; the eye-catching turrets; the detailed terra-cotta ornament, and intricate brick and stone patterns.

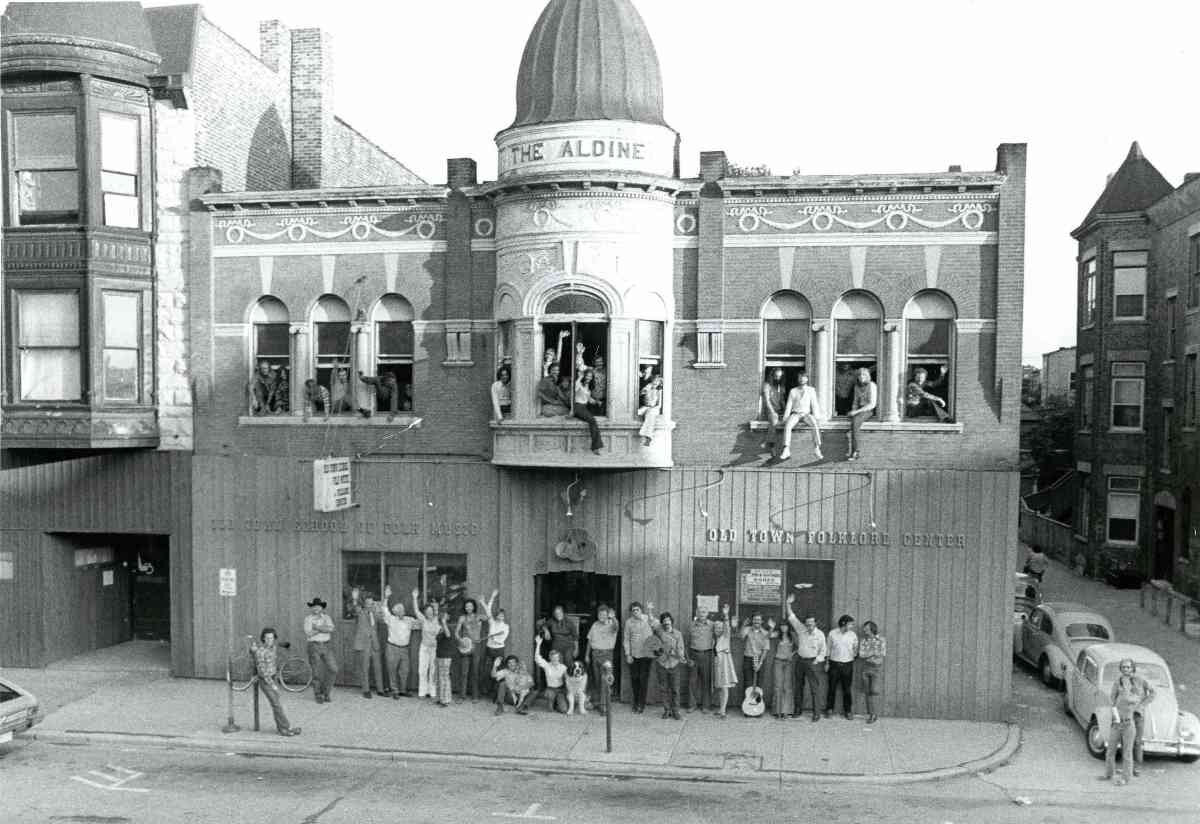

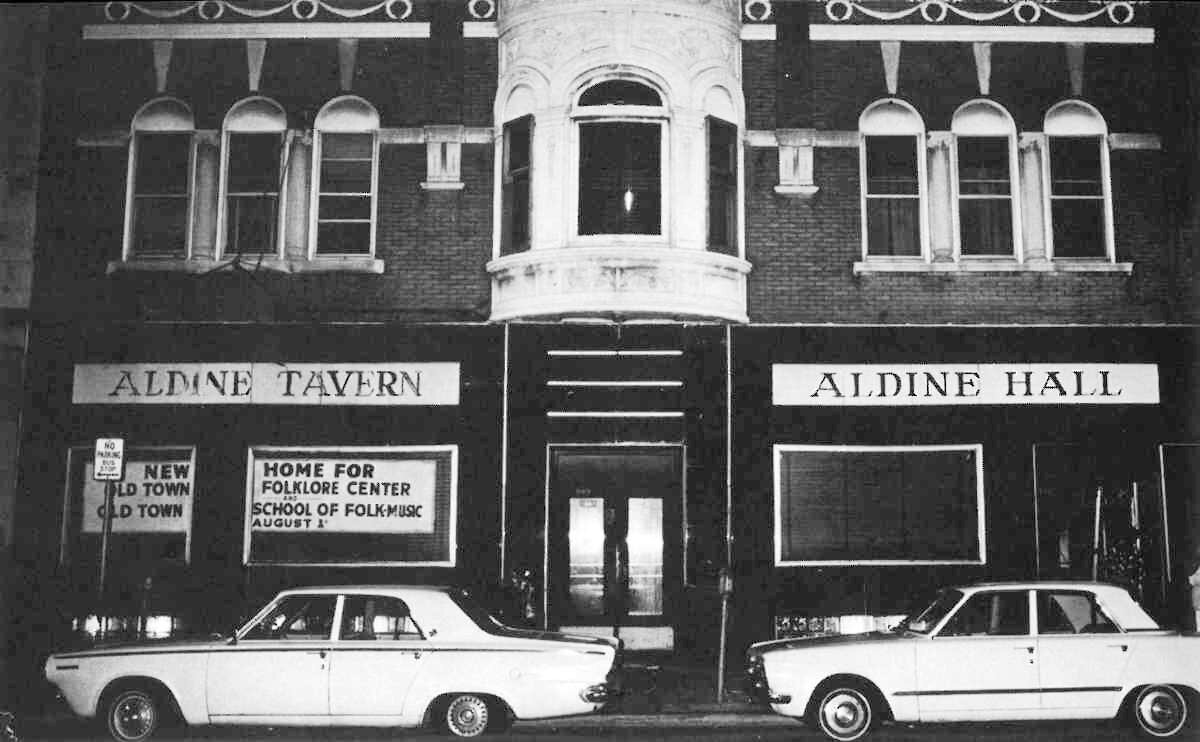

Perhaps the most well-known building in the entire district is the Aldine Building at 909 W. Armitage (designed by Joseph Bettinghofer, 1896). The Aldine is the only Romanesque Revival-style building in the neighborhood and Bettinghofer was likely thinking of a German version of Romanesque Revival from the 1830’s known as Rundbogenstil (or “Round-arched style”) visible here in the semi-circular windows in the entranceway and on the second floor. In the 1930's Aldine Halls and Tavern occupied the first floor; the owner lived above. In 1968 the Old Town School of Folk Music moved in. A few years ago the school relocated to Lincoln Avenue, but the Aldine remains home to the Folk Music School's youth program.

When I first moved to the Armitage Halsted area, Shinnick Drugs was the local pharmacy and a neighborhood anchor located on the corner of Armitage and Bissell. Interestingly I found an old photograph showing that the same retail location was also a pharmacy, J. E. Voigt & Sons all the way back in 1895; probably the first retail tenant when the building was constructed! I made a “Then and Now” comparison photograph (see below). When Shinnicks finally closed (a sad day) a local boutique, Art Effect, moved in but thankfully they left the old glass Hydrox/Sealtest Ice Cream signs embedded in the windows above the entryway.

The Armitage Halsted Historic District is often painted in nostalgic, turn-of-the-century architectural tones; however, history is hardly that tidy. Early in the twentieth century the tightly knit German community began to dissolve as Italians, Poles and other ethnic groups began to move into the neighborhood, many drawn by jobs at the factories lining the Chicago River less than a mile to the west. Many of the German residents re-located to the north along Lincoln Avenue.

When the Depression hit the country the well-kept housing stock in Lincoln Park began to fall into disrepair. Although the economy began to recover during WWII, many of the homes became boarding houses for the single men working in the nearby war-effort factories. By the 1950’s the western half of the Lincoln Park area became run-down.

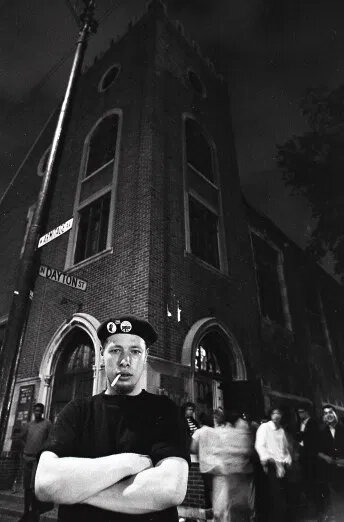

The area around Halsted and Armitage attracted many Puerto Ricans beginning around 1960. A series of gentrification efforts had chased the Puerto Rican community from the Near West Side and Garfield Park to the Near North Side along Clark Street, which became known as La Clark. With the construction of Sandburg Village, many in the Puerto Rican community moved to the neighborhood centered around Armitage and Dayton. The Armitage Avenue Methodist Church on the northwest corner became a central gathering spot.

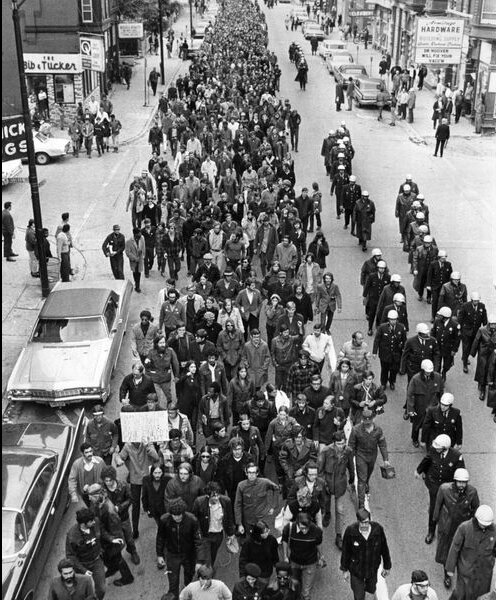

To defend their turf younger Puerto Ricans started the Young Lords which was more like a social revolutionary group modeled after and aligned with the Black Panthers rather that a street gang. Jose “Cha-Cha” Jimenez was their charismatic leader and he’s seen in one of the photographs below in front of the Methodist Church at Armitage and Dayton. However, strong forces were aligned against the Puerto Rican community and despite protests (including a march down Armitage Avenue - see below) and support from some neighborhood groups the Puerto Rican community was displaced yet again and over the next half century the neighborhood has become one of the wealthiest areas in the city, and the nation actually.

The wide arc of change has delivered a rich architectural, social and economic history to a small neighborhood in Chicago. Stop by and explore.

Bonus: below is a random collection of other photographs of the district I’ve taken over time.